“I think human consciousness is a tragic misstep in human evolution. We became too self aware; nature created an aspect of nature separate from itself. We are creatures that should not exist by natural law. We are things that labor under the illusion of having a self, a secretion of sensory experience and feeling, programmed with total assurance that we are each somebody, when in fact everybody’s nobody. I think the honorable thing for our species to do is deny our programming, stop reproducing, walk hand in hand into extinction, one last midnight, brothers and sisters opting out of a raw deal.”

― Rustin Cohle: True Detective Series

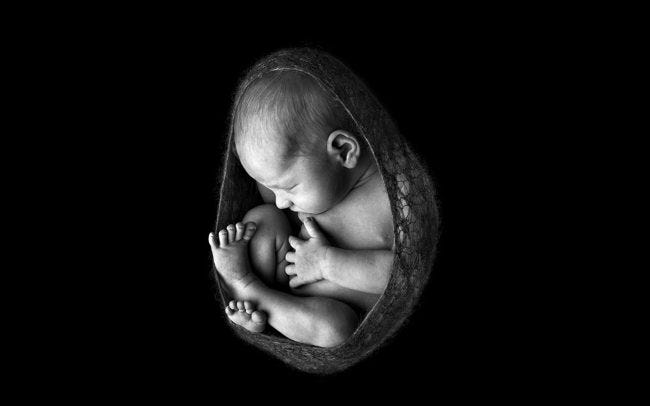

Antinatalism is a philosophical stance that contends that bringing new people into existence is morally indefensible, because the inevitable harms of existence outweigh any potential benefits. This viewpoint, which have been defended extensively in David Benatar’s book Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence, challenges the widely held belief that life is a gift or a blessing. Instead, it posits that non-existence is preferable to existence, particularly when viewed through the lens of suffering, ethical responsibility, and the asymmetry of harm.

In this essay, I will outline the core tenets of antinatalism, provide a defense of its principles, and address some of the common objections that are often raised against it. To do so, I will focus on the asymmetry between pleasure and pain, the inevitability and depth of human suffering, the absence of consent in bringing new life into existence, and the myth of the so-called "good life." Ultimately, I will argue that, given the harms of existence and the inability to justify procreation ethically, the only responsible and compassionate choice is to refrain from bringing new people into existence. Ultimately, I will argue that non-existence is preferable to existence, at least when measured by the weight of suffering that living beings are inevitably exposed to.

The Asymmetry Between Pain and Pleasure

Central to antinatalism is what is called the asymmetry between pain and pleasure. This asymmetry forms the foundation of the argument that bringing new life into existence is inherently problematic. To grasp this idea, we must consider how pain and pleasure relate to one another, particularly when evaluating whether a life is worth bringing into being.

On the one hand, the presence of pain is a bad thing. This is largely uncontroversial—most people would agree that pain, suffering, and distress are undesirable and that, all else being equal, it is better not to experience them. On the other hand, the presence of pleasure is generally considered a good thing. But here lies the first point of asymmetry: while the absence of pain is necessarily good (even when there is no one to benefit from that absence), the absence of pleasure is not necessarily bad, provided that there is no one who is deprived of it. In other words, not existing means being spared from the pain and suffering of life, which is a clear benefit. However, the non-existent do not miss out on pleasure because they do not exist to experience that deprivation. This creates an inherent asymmetry in evaluating existence.

Consider this simple formulation:

Presence of pain is bad.

Presence of pleasure is good.

Absence of pain (for a non-existent person) is good.

Absence of pleasure (for a non-existent person) is not bad, because there is no one for whom it is a deprivation.

This asymmetry reveals that while avoiding pain is always beneficial, failing to create new pleasure (in the form of a new life) is not harmful. Thus, bringing someone into existence exposes them to the risk of pain and suffering—something undeniably bad—while the supposed benefits of life (pleasure) are not missed by the non-existent. Therefore, it is better not to bring new lives into existence because they are spared the inevitable suffering of life without losing anything by never experiencing its pleasures.

To put it differently, the presence of suffering in life is a harm that cannot be justified by the potential for happiness. Even if someone were to experience a life filled with pleasure, that pleasure does not outweigh the fact that, in order to experience it, they must also endure suffering. The asymmetry between pain and pleasure thus forms the foundation of the antinatalist argument: it is better not to exist because, in non-existence, there is no harm, while in existence, harm is inevitable.

The Ubiquity of Suffering

Human life is punctuated by both pleasure and pain, but the experience of suffering is an inescapable feature of existence. From birth to death, individuals are exposed to a range of harms that make life difficult, painful, and, in many cases, unbearable. This suffering comes in many forms: physical pain, psychological distress, existential angst, and ultimately death, which is itself a form of suffering due to the anxiety it provokes and the loss it represents. While some may argue that the joys of life—love, friendship, accomplishment—balance out the pains, I contend that suffering is an unavoidable and deeply pervasive aspect of human existence.

First, there is the suffering that arises from our physical nature. Our bodies are fragile and vulnerable to illness, injury, and aging. No matter how fortunate one may be in avoiding serious illness or accident, the decay of the body is inevitable. Pain, disease, and the limitations of physical aging are intrinsic features of human life, and none of us can escape them.

Beyond the physical, there is the psychological and emotional suffering that comes with human consciousness. Self-awareness brings with it the ability to reflect on our own mortality, to experience grief and loss, to endure anxiety, depression, and despair. Even those who lead relatively happy lives experience moments of profound emotional suffering. We experience heartbreak, disappointment, frustration, and fear. We struggle to find meaning in a world that is indifferent to our existence and are haunted by the knowledge that all of our efforts and achievements will ultimately be rendered meaningless by our death.

Suffering, then, is not an aberration or a minor inconvenience in the human experience—it is the very fabric of existence. While some may argue that suffering is necessary for growth, or that it can be outweighed by moments of happiness, I contend that the magnitude and inevitability of suffering far exceed any potential benefits that life may offer. Moreover, it is important to recognize that suffering is not evenly distributed; many people endure lives filled with more pain than pleasure, and even those who are relatively well-off cannot escape the eventual suffering of death.

Importantly, suffering is not an aberration or an accidental feature of existence—it is built into the very structure of life. Our biological needs, the social pressures we face, and the existential challenges of self-awareness all ensure that suffering is inescapable. To procreate, then, is to condemn another being to the inevitability of suffering.

The Consent Problem

Another crucial element of the antinatalist argument is the issue of consent. Procreation imposes life on someone who has no say in whether or not they want to be brought into existence. When we decide to create a new life, we are effectively making a decision on behalf of someone else—one that has profound and irreversible consequences. Once a person is born, they must endure the burdens and harms of existence, and they have no ability to opt out of this reality (except, perhaps, through the tragic act of suicide, which itself involves suffering).

In most other areas of moral life, we recognize the importance of consent. We understand that it is wrong to impose significant harm or risk on others without their permission. Yet, in the case of procreation, we disregard this principle entirely. We bring new people into the world without their consent, subjecting them to the inevitabilities of suffering, hardship, and death, all without giving them a choice in the matter.

Some may object that we cannot ask the non-existent for their consent, because they do not yet exist. But this is precisely the point: since they do not exist, there is no moral obligation to bring them into existence. By choosing not to procreate, we avoid imposing harm on a being that would otherwise have no say in the matter. The ethical default, in light of the consent problem, should be not to create new life. We cannot justify the imposition of suffering and harm on another being simply because we wish to bring them into existence.

The Impossibility of Harm to the Non-Existent

A common objection to antinatalism is that choosing not to procreate deprives potential individuals of the chance to experience the joys of life. However, this objection is misguided because it overlooks a crucial aspect of non-existence: there is no one who is deprived of anything. Non-existence is not a state of being; it is simply the absence of being. There is no "potential person" who is waiting in the wings, eager to experience life but cruelly denied the opportunity by our choice not to reproduce. The non-existent do not suffer from not being brought into existence.

In contrast, bringing someone into existence introduces the very real possibility of harm. Once born, a person is exposed to all the sufferings and miseries that life entails. While they may also experience pleasures, the balance of their life is still skewed towards the negative because of the inevitability of suffering. This suffering is made worse by the fact that the person never had a choice in the matter—they are simply forced to endure the life that was imposed upon them. By choosing not to procreate, we spare the non-existent from all harm and deny them nothing.

The Myth of the "Good Life"

One of the most common objections to antinatalism is the claim that life is generally good, or that most people lead lives that are worth living. According to this view, while life may contain suffering, it also offers pleasures and rewards that make existence valuable. Many people believe that the joys of life—love, friendship, accomplishment—outweigh the harms, and therefore procreation is morally justified.

However, this argument is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of human life and the psychological biases that distort our perception of well-being. Humans are naturally inclined to engage in what psychologists call “the optimism bias,” a cognitive distortion that leads us to overestimate the likelihood of positive events in our lives and underestimate the prevalence of negative ones. We are also prone to rationalization and cognitive dissonance, convincing ourselves that our suffering is worthwhile or that our hardships have made us stronger.

While it is true that some people experience moments of joy and fulfillment, these moments are often fleeting, conditional, and far outweighed by the burdens of existence. Moreover, the supposed “goods” of life—love, family, success—are often accompanied by their own forms of suffering. Love, for example, can lead to heartbreak, loss, and grief. Family can bring conflict, disappointment, and responsibility. Success is often followed by anxiety, stress, and the fear of failure.

Even if a person leads what they believe to be a good life, the fact remains that their existence is punctuated by suffering, and it will ultimately end in death. Death, in itself, is a harm, both because of the fear and anxiety it provokes and because it represents the loss of everything a person has worked for and loved. No matter how good one’s life may seem, it is always overshadowed by the inevitability of death and the suffering that comes with it.

The notion of a “good life” is therefore largely a myth, sustained by psychological biases and cultural narratives that obscure the harsh realities of existence. When we consider life without these distortions, we see that suffering is not an occasional feature of life but its constant companion. Given the ubiquity of suffering and the finality of death, it is difficult to justify the claim that life is, on the whole, a good thing.

Moral Responsibility and the Ethical Case for Antinatalism

If we accept the antinatalist view that existence is characterized by suffering and that non-existence is preferable to life, then we must also recognize the moral responsibility that comes with this realization. As individuals, we have an ethical duty to prevent harm when we can, and procreation undeniably imposes harm on new beings. To bring a new person into existence is to subject them to the inevitabilities of suffering, hardship, and death, all of which could be avoided by simply choosing not to procreate.

Some may argue that parents can mitigate the harms of existence by providing their children with love, care, and support. While it is true that loving parents can alleviate some forms of suffering, no parent can protect their child from all the harms of life. Parents cannot shield their children from illness, loss, emotional distress, or the reality of death. By creating new life, they are guaranteeing that their children will one day experience suffering, and they cannot control the extent or severity of that suffering.

Moreover, the decision to procreate is often made for selfish reasons. People have children because they desire the experience of parenthood, because they want to pass on their genes, or because they feel societal or familial pressure to reproduce. These motivations, however, do not justify the imposition of harm on another being. In making the choice to procreate, we are prioritizing our own desires over the well-being of the person we bring into existence. If we take seriously the moral principle that we should not cause unnecessary harm, then we must conclude that it is wrong to create new life.

What Antinatalism Is Not

Antinatalism is often misunderstood and mischaracterized. I make clear that antinatalism is not an endorsement of suffering, despair, or hopelessness. Rather, it is a rational, ethical stance grounded in compassion and the desire to prevent harm. To clarify further:

1. Antinatalism is not misanthropy: It does not arise from a hatred of humanity or a desire to see others suffer. In fact, it is precisely because of empathy and concern for future beings that antinatalists argue against bringing new life into existence. The position is driven by a desire to prevent suffering, not a disdain for human life.

2. Antinatalism is not suicidal: It does not suggest that those who already exist should end their lives. Life, for those who are already born, can be complex and filled with attachments that make suicide a tragic and harmful option. Antinatalism seeks to prevent new beings from experiencing the inevitable harms of life, not to advocate for ending lives already underway.

3. Antinatalism is not nihilism: It does not claim that life has no value or meaning. Antinatalists recognize that life contains moments of joy, love, and meaning. However, they argue that these moments do not outweigh the profound and unavoidable suffering that characterizes human existence. Antinatalism questions the ethical justification of creating new life, not the worth of the lives that already exist.

4. Antinatalism is not anti-progress: It does not oppose efforts to improve life for those already living, nor does it deny the importance of social justice, scientific advancement, or the alleviation of suffering. Antinatalists fully support efforts to reduce the harms of existence but contend that the most effective way to prevent suffering is to avoid bringing new people into a world where harm is inevitable.

Antinatalism is a compassionate, ethical stance focused on harm prevention. It is often misunderstood as pessimistic or anti-life, but it is, in fact, a rational position aimed at sparing potential beings from the deep and unavoidable harms of existence.

Antinatalism is not a rejection of life, but a recognition of its inherent suffering and the moral responsibilities that come with that recognition. By embracing antinatalism, we are acknowledging the deep asymmetry between pain and pleasure, the pervasive nature of suffering, and the ethical problems associated with procreation. We are also recognizing the rights of future beings—not by bringing them into existence, but by sparing them from the harms that life inevitably entails.

In light of these considerations, the only morally responsible course of action is to refrain from procreating. By doing so, we can prevent harm and uphold our ethical duty to future generations, who, by not existing, will be spared the burden of life’s suffering. While this view may be unpopular and unsettling to many, it is a conclusion rooted in reason, compassion, and a clear-eyed view of the human condition.

Thought provoking, unsettling, yet sensible. It's gonna be hard to come to terms with, but....

Procreation is born out of selfish intentions. It's that simple.

This is the most detailed piece I've read on this subject. Thanks for this.